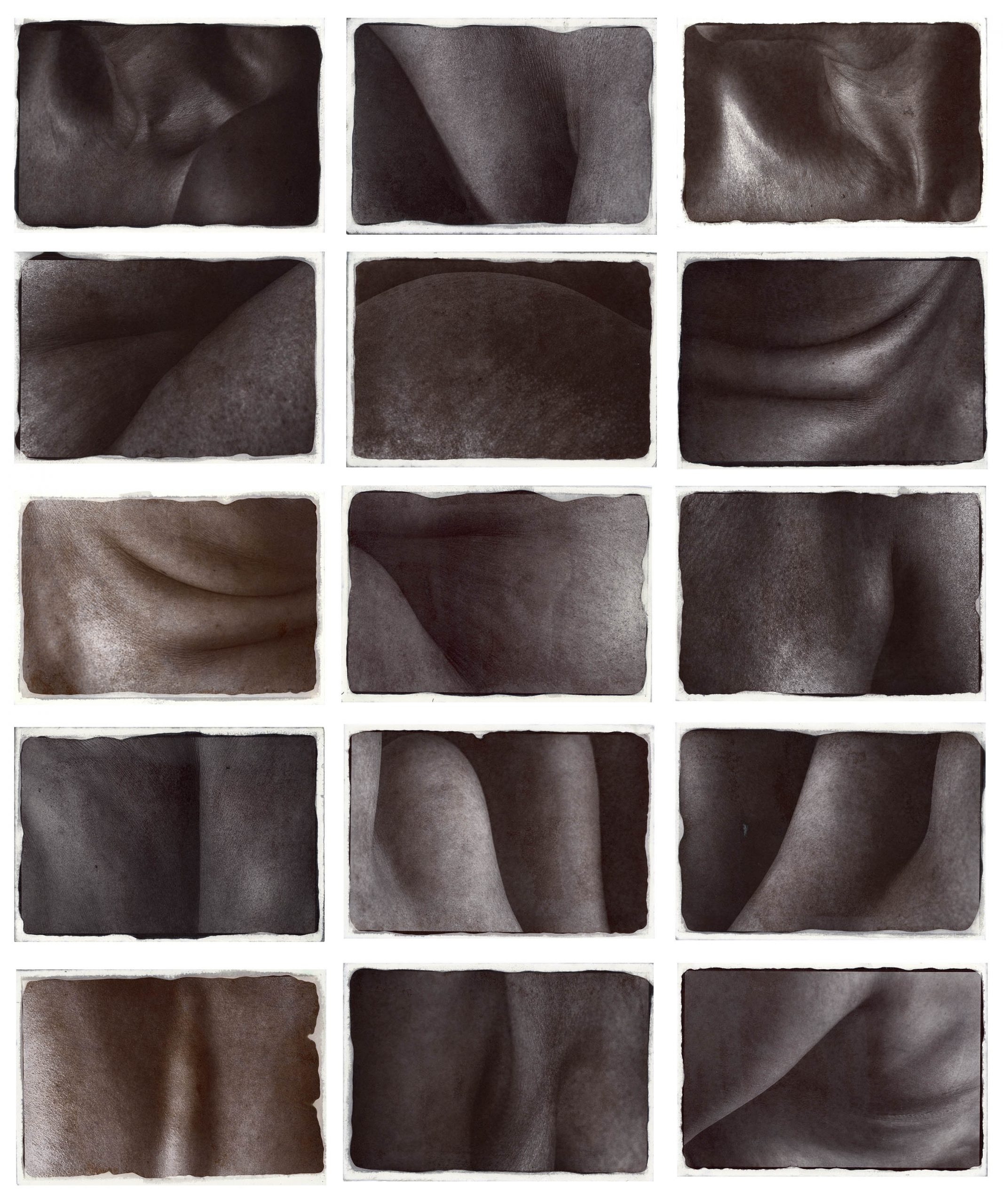

Philippe Calia

‘Spill Over’ from the series The Shape of Clouds (2021)

Disused Copper-Mine Tailing Pond, 55°34’13’’ N / 59°49’27” E, Levikha, Russia (2019)

Printed on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Metallic, 42 x 28 inches

Art remains in the artist and is the knowledge by which things are made.

– Ananda K. Coomaraswamy

How do we trace the origins of the image world and what is the underlying psychology of visual perceptions? Can we think of the scripted word, as many semioticians have, in creating an image in the mind as the moment of inception?

Four decades ago, at the conclusion of his paradigmatic reflections upon the essence of what was to become the world’s most accessible and influential medium of visual communication, Roland Barthes declared that it was a subjective decision to receive images as either reality or illusion. [i] Writer/editor/curator, Fred Richtin asked, “Should the photograph be labelled, like writing, as either fiction or non-fiction or are they always a hybrid of the two?” [ii] and Rushdie, as quoted by author Amitava Kumar suggests while looking at identity imagery, “the very word metaphor, with its roots in the Greek word for bearing across, describes a sort of migration, the migration of ideas into images.” [iii] Their stark enunciations of the viewer’s responsibility is especially resonant today for artistic and other purposes – transforming, and thereby crucially redefining, the very categories upon which we base our understanding of the world: ‘imagined’ and ‘factual’, ‘appearance’ and ‘actuality’.

In the last decade, there has been an exponential ‘rediscovery’ of analogue media as a means to the foreground, once again, found or constructed intangibilities of the human condition. The printed image on a surface or imprinted in memory – both organic strata – both produced through the sensorial, the shared intelligence of data transfers, creates an arena for theoretically engaging with discursive and real shifts in the present media environment. Early modernists on the other hand, such as László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) [iv] and Lionel Wendt (1900-44) [v] in Sri Lanka, had experimented with the medium – camera-less photography and multiple exposures, among other techniques – as a way to document the mysteries of nature, to introduce poetic disorder into normative frames, to interrogate viewing habits and to play with perception itself.

Two recent international exhibitions/publications, Memory of the Future (2016) and The Shape of Light (2018) have conceptualized past and contemporary experimental techniques from a European perspective, but relatively little has been published on South Asian developments in this area. [vi] However, important regional trajectories of innovative photo-making are starting to be mapped through the work, for instance, of Film Foundry in Nepal, O.P. Sharma in Delhi, Pathshala in Dhaka and the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad. [vii] Kamra 1 and 2, anthologies of studies of photography published in Bangla, look at histories and theories of representation; also notable is the pioneering scholarship and image archive of Siddhartha Ghosh (1948-2002), who traced the history of photography in Bengal, including the contribution of women photographers, during the period of colonial modernity. [viii] Another valuable initiative is the Afghan Box Camera Project. [ix]

As evident in the works featured here, contemporary practitioners in South Asia (in this case, India) have continued their pursuit of hybrid forms and upheld a passionate interest in global as well as local photographic histories, in the face of ongoing international debate about diktats of technology and the effect of post-digital image surfeit upon creativity, viewership and methodologies of curation. While preparing for this exhibition I drew upon my involvement in The Surface of Things (2016-17), presenting strategies and techniques of reconsidering the significance of personal, family and community archives in relation to material culture. [x] It also provoked me to consider the structure of the modern photography canon, which has reset its parameters and become more inclusive through the expanded autonomy and frequent iconoclasm of new-media/mixed-media interventions. This is a prominent aspect of Unsealed Chamber: the dialectical works featured here are precisely themed and framed, yet rely on their effect on their aura of ambiguity, ambivalence, equivalence. Alternating between fixity and fluidity, permanence and transience, they demand that we decode, as best as we can, the unconventional grammar being continuously shaped within technologically-driven current photography discourses.

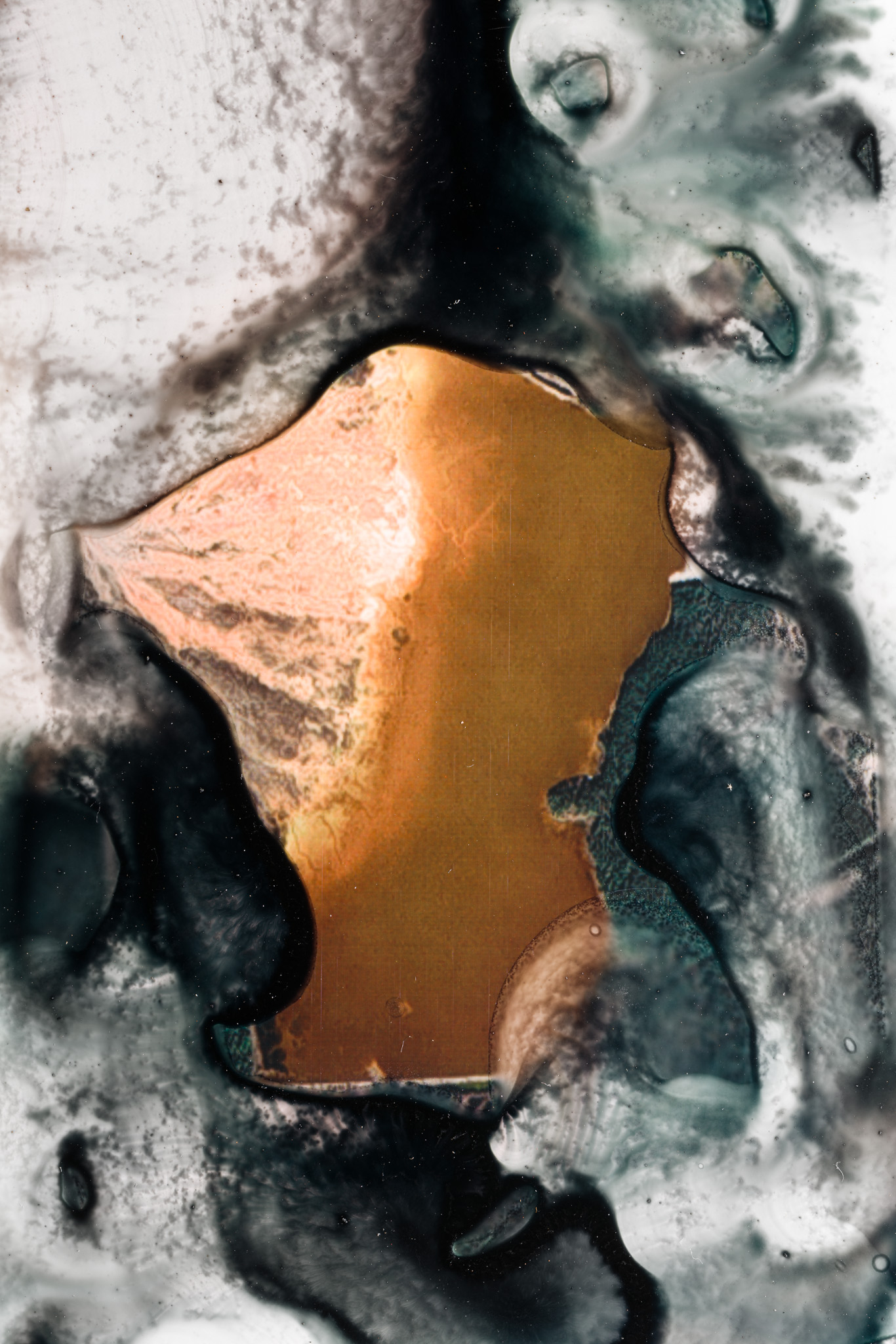

Aparna Nori

From the series Nalla Pilla (2021)

Mosaic of Gold-Borax toned Salted Paper Prints,

7 x 10 inches each

Aparna Nori’s images arrive within the dual complexes of the science of the body and the science of photo-making. Nalla Pilla (Telugu:‘Little Dark Girl’) records details of Aparna’s body, its shades and its textures. Drawn from a series of recollections and visible scars upon the body – perhaps resonant of violations, but also societal imbalances, unethical treatments – Aparna’s visualization of blemish and skin gradient coax the suppressed anxieties to light. Presented eventually as salt paper photographs housed in a self-contained, self-lit frame, the object becomes a vessel, enshrining the body as a sacred entity, using the skin as its language. The surface of the print, much like an outer layer, another skin, speaks of gradations of life’s experiences. Flesh as voice, as memory, as destiny; the speech acts of nodes, glands, ducts, folded into the tireless webbing of muscle, sinew, ligament tendon, cartilage – incising, etching, reciting. The parallel incarnation of a digital projection of performance presents the compulsive act of recounting all that’s in mind and speaks of the artist as a scripter, recorder, and emissary.

The creative process placed me in the roles of performer-spectator as I attempted to project the discomfort and trauma, the coercions of the external gaze and of the actions imposed upon me.

Aparna Nori, Artist Statement.

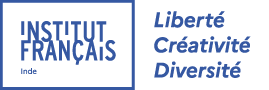

Philippe Calia

‘Memory Hole (#3)’ from the series The Shape of Clouds (2021)

Rare-Earth Mine Tailing Pond, 35°29’03’’ N /

115°32’54” W, Mountain Pass, USA (2012)

Inkjet print on Washi Murakumo Kozo Natural Paper,

6.7 x 10 inches

We ‘zoom out’ into the dialectic of suture/rupture in Philippe Calia’s delineation of the environmental damage, the trauma wreaked by extractive commercial mining, including for the very elements used in digital imaging technology. His meta-textual narrative that reworks the unified grids of satellite surveys of the earth is a synoptic of brutal corporate profiteering, ecological and community destruction, and the sheer, unrelenting toxicity of particular industrial processes, underpinned by equally toxic economic practices. Like ooze from a septic wound, lethal poisons clog and overflow the shallow craters used for dumping waste and runoff. A dissonant counter-narrative is provided by way of a video work that ‘mines’ the terrain of interiority/memory via the harmonizing apparatus of nostalgia: family bonds, childhood wonder and dismay.

I reproduced and then reworked the smooth aerial images of these sites, washing and degrading them to produce new landscapes.

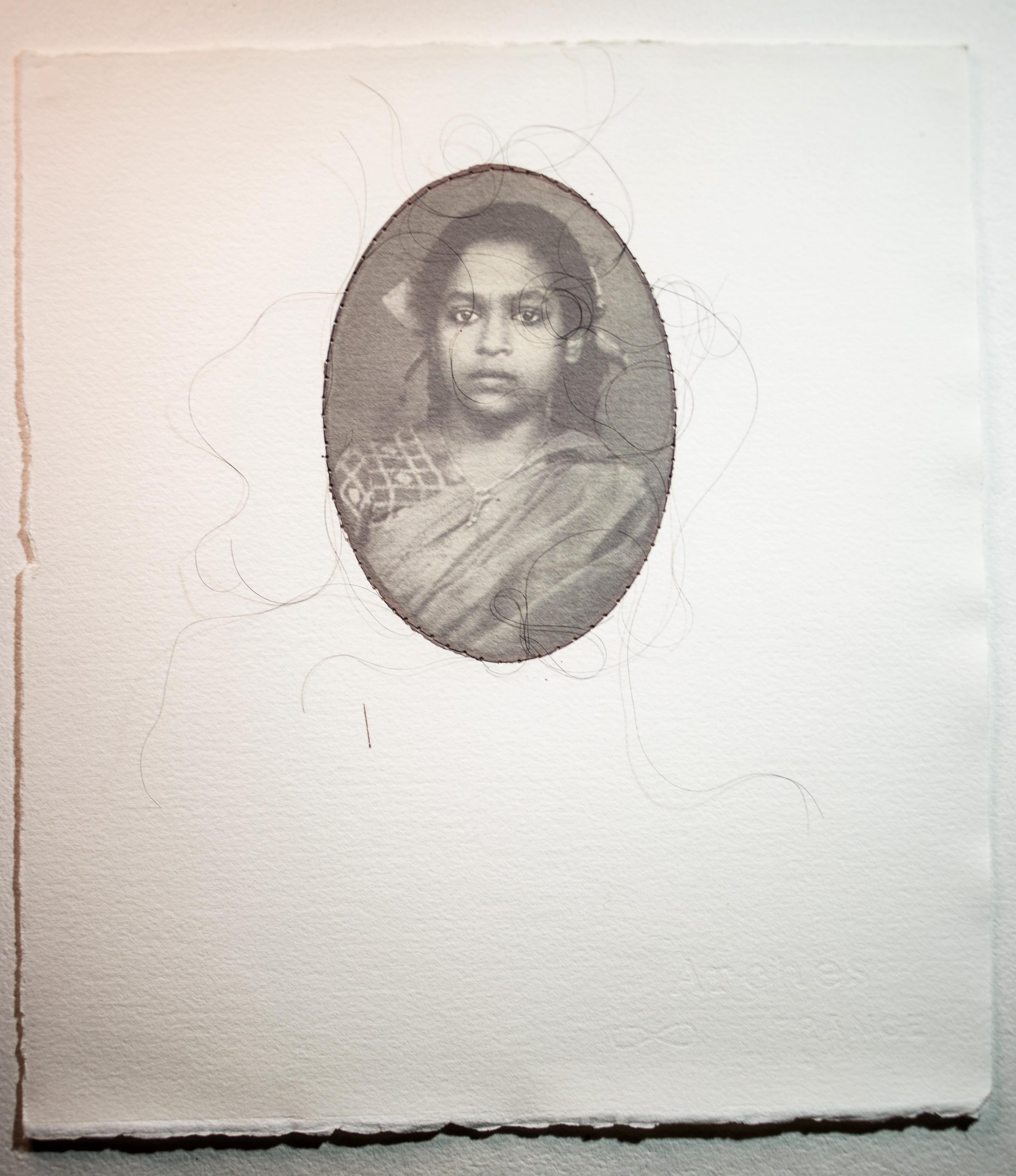

Indu Antony

From the series Ivar (2021)

Salted Paper Print, 10 x 11 inches

We immerse in the dialectic of visibility/invisibility as projected via Indu Antony’s work Ivar (Malayalam: ‘Them’, referring to people within one’s home/vicinity). Her initial probing of the relationship between self-expression and found objects – discarded photographs of anonymous women collected over time – led to a sustained project of salvaging occluded individual presences, vanished lives that can be acknowledged, valued and celebrated if someone persists in seeking them out. Printed in familiar oval format, much like the vintage portraits of our grandparents and other elders, these unknown genealogies are showcased as a series of salt prints, a medium that fades over time. But the eventual erasure of these already spectral subjects is actively countered by their material framing: strands of human hair that will remain after the gradual dissipation of the chemical surface, and the unique imprint of the person it once hosted.

… a form of presence purely dedicated to the inscription of absence, and as a witness to/testimonial of our existential fragility.

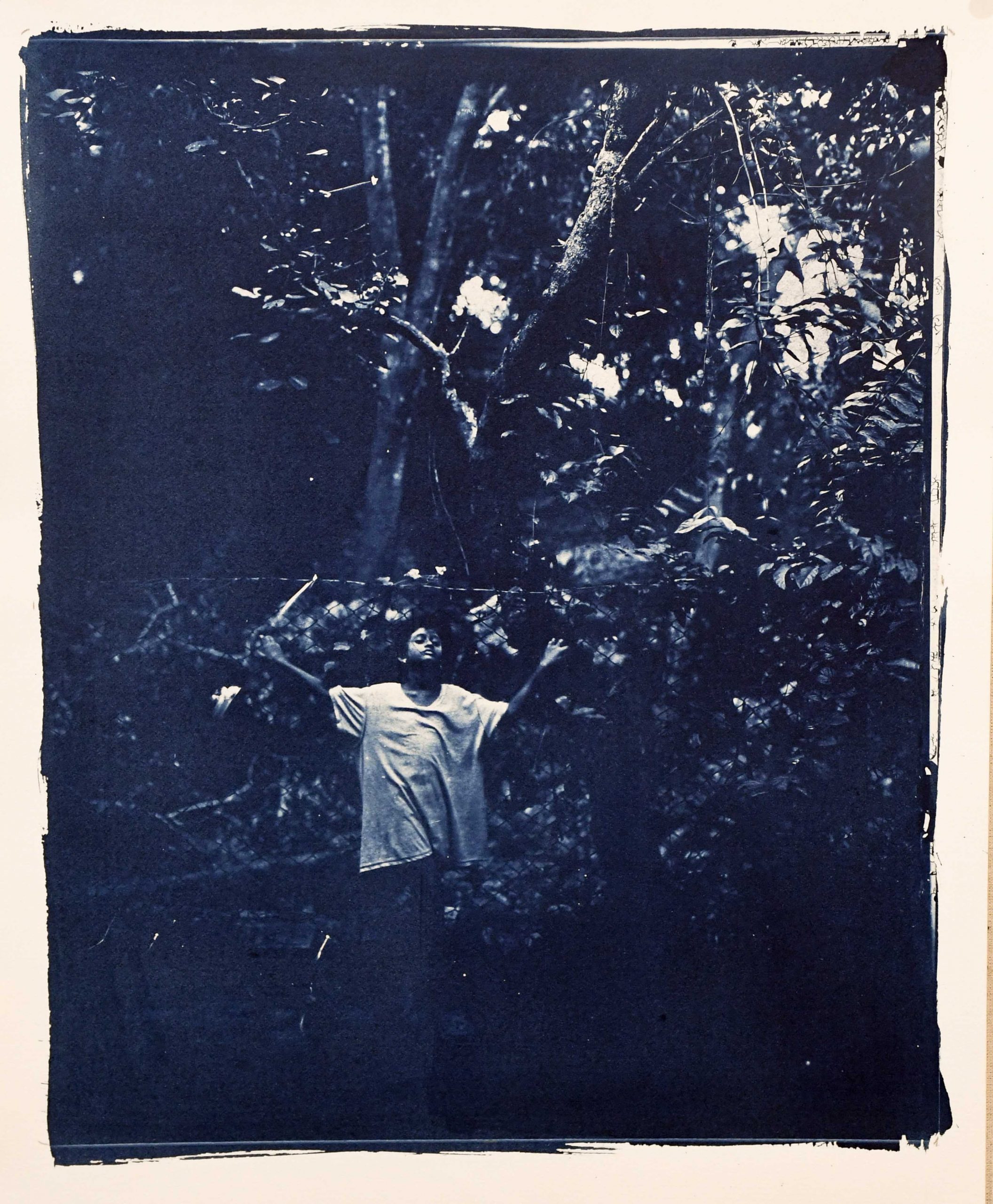

Arpan Mukherjee

From the series Gola Vora Dhan (2013-21)

Cyanotype from Glass Plate Collodion Negative on Paper, 15 x 11 inches

We emerge into the dialectic of belonging through Arpan Mukherjee’s enigmatic works that urge us to reflect on the much-theorized relationship between photography and time. The ambiguous contours, bring to light a narrative of migration, and of remembering. They seem to ask, with regard to the photograph as a personal, familial and social document: Can there be an ‘event’ in the absence of a witness? Can there be ‘testimony’ in the absence of a listener? Do photographs reverse the flow of recollection, and actually block memory, or become a counter-memory? Are photographs fundamentally deceptive, always cheating us of our need for authentication – of the self, of the world? Is our understanding of an event transformed when our memory of it is overlaid by a photograph of it? Do the boundaries of our existent memory of an event extend beyond the edges of a photograph of the event?

The very process of image-making allows for its imperfections to be visible, and compels us to acknowledge that repeated manual printing never yields the same result.

Arpan Mukherjee, Artist Statement.

Through their composite techniques, the four artists featured in this exhibition persuade us into less familiar modalities of engaging the world: attenuation, gradation, diffraction, obscurity, eclipse. Abstraction is embodied, and embodiment abstracted, They ask: What do photographs encage, what do they release within the viewing experience? Why is it so unsettling to navigate the chasm between the fixed photographic self and the living experiential self? Given the aggressions of our digital ethos, are photographs altering the human capacity to remember without the support of visual artefacts? And is it truly impossible to remember something without reference to a corresponding internal or external image?

[i] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, tr. Richard Howard (Hill and Wang, 1981). [ii] Fred Ritchin, Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen (New York: Aperture, 2013), p.26. [iii] Amitava Kumar, Passport Photos (University of California Press, 2000). [iv] Born in 1895 in Borsód, Austria-Hungary, László Moholy-Nagy “believed in the potential of art as a vehicle for social transformation, working hand in hand with technology for the betterment of humanity. A multifaceted artist, educator, and prolific writer, Moholy-Nagy experimented across mediums, moving fluidly between the fine and applied arts, pursuing his quest to illuminate the interrelatedness of life, art, and technology. Among his radical innovations were his experiments with cameraless photographs (which he dubbed ‘photograms’); unconventional use of industrial materials in painting and sculpture; experiments with light, transparency, space, and motion across mediums; and his work at the forefront of abstraction… Moholy-Nagy always sought out new materials and methods in the steadfast belief that the assimilation of art, technology, and education could be an essential tool for communication and the dissemination of information.”

Source: https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/laszlo-moholy-nagy [v] Lionel Wendt “carved an influential legacy in Sri Lanka as a photographer, concert pianist, critic, and founding member of the 43 Group, assembling modernist artistic practitioners who steered away from the academic style and Victorian naturalism dominant in the colonial period. Wendt’s family was of Dutch descent and he initially trained as a lawyer in England before returning to Sri Lanka, where he took up the camera and co-founded the Photographic Society of Ceylon… His experiments with photography included the use of montage and solarization. Wendt created intimate portraits of male and female subjects, presenting them as vulnerable and performative bodies, while also candidly addressing sexuality in these images.” Excerpted from Natasha Ginwala, “Lionel Wendt (1900-44)”, text accompanying Wendt’s works at Documenta 14, Athens and Kassel (2017).

Source: https://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/16244/lionel-wendt. [vi] Exhibition catalogues: The Memory of the Future: Photographic Dialogues between Past, Present and Future, ed. Tatyana Franck (Noir sur Blanc and Musée de l’Elysée, May 2016) and The Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art, eds. Simon Baker and Emmanuelle de l’Ecotais with Shoair Mavlian (Tate Publishing, 2018). [vii] See https://www.filmfoundry.org/; https://pathshalainstitute.org ; https://www.nid.edu/home [viii] The Kamra anthologies are published by Tanzim Wahab and Munem Wasif. Source: https://pathshalainstitute.org/faculty/photography/tanzim-wahab. For detailed information on Siddhartha Ghosh’s seminal contributions to modern South Asian photography discourse, see https://quod.lib.umich.edu/t/tap/7977573.0004.202/–zenana-studio-early-women-photographers-of-bengal?rgn=main;view=fulltext; also see https://asapconnect.in/post/230/singlestories/siddhartha-ghosh-interviews-sunil-janah [ix] “This project was initiated early in 2011 by Austrian artist Lukas Birk and Irish ethnographer Sean Foley. The aim of the project from the outset was to create an urgent record of the disappearing art of Afghan box camera photography and make that information freely available online for all.” http://www.afghanboxcamera.com/. For a detailed account by the project’s co-founders, also see http://www.enterpix.in/feature/renewal-afghanistan/afghan-box-camera-project/ [x] In 1826, experimentation with a light-sensitive surface led French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765-1833) to take the first photograph (a heliograph) – a view seen through a window – at his country estate. Almost two centuries later, as part of a festival of photography during Bonjour India 2017-18, that paradigmatic first image was commemorated via The Surface of Things, a process-oriented exhibition featuring the innovative cross-media works of four contemporary artists: Uzma Mohsin, Srinivas Kuruganti, Sukanya Ghosh and Edson Dias. With support from Alliance Française de Delhi and Institut Français, the show was held at Alliance Française de Delhi, New Delhi (24 November – 13 December 2016) and the Dr Bhau Daji Lad City Museum, Mumbai (20 August-19 September 2017). For installation views and further details, see https://alkazifoundation.org/the-surface-of-things-photography-in-process-2/